Topic: the link between conflict and the mining industry

- What are “conflict minerals” or “blood minerals”?

- Is the extraction of these minerals the cause of the conflict?

- How is a mine certified? How does a certified mine differ from one which is not certified?

- Does certifying minerals at source work? What progress has been made? What still needs to be done?

- Are conflict minerals only in Africa?

Topic: The consumption of technology and consumer responsibility

- What electronic devices are manufactured using these minerals?

- What is a supply chain?

- Is there a certificate that guarantees me “100% conflict-free” electronic products?

- How can I know if a company is behaving responsibly with regard to the issue of “conflict minerals”?

- Can a mobile phone be made without “conflict minerals”?

- What product (mobile phone, computer, etc.) will I buy?

- Where can I bring my phone/computer/tablet to be recycled?

- How I can get one of your boxes for recycling mobile phones?

Topic: Legislation on conflict minerals

- Why is it necessary to regulate global trade?

- How can trade in “conflict minerals” be regulated?

- Is European law enough to bring an end to the humanitarian crisis in eastern DR Congo?

What are “conflict minerals” or “blood minerals”?

In the broadest sense, they are all minerals whose extraction or trade takes place in a context of conflict and which may be linked to the violation of humanitarian law or to violations which may be considered war crimes.

However, in the case of international regulations, the definition of “conflict minerals” is restricted mainly to four minerals: tin, tungsten (extracted from wolfram), tantalum (extracted from coltan) and gold. These are known as 3TG minerals and their extraction and unlawful trade has been linked to the financing of armed groups and/or organised crime in places such as the east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and some areas of Colombia.

Other minerals, metals and rare earth elements are found in our electronic devices which are equally problematic at their extraction sites. For this reason we believe that it would be desirable for international regulations to include in their definition of “conflict minerals” all those raw materials of mineral origin which are linked to human rights violations.

Is the extraction of these minerals the cause of the conflict?

Not necessarily. It is true that there is evidence linking the natural resources and the armed conflicts. For example, a report from the United Nations Environment Programme recently estimated that since the 1990s at least 18 violent conflicts have been fuelled by the mining of natural resources (diamonds, oil, gold, wood, minerals); and about 40 percent of all intra-state conflicts over the past sixty years can be linked to disputes over the control of these resources.

However, there are other factors which affect the outbreak and prolongation of a conflict over time. These include institutional weakness, political corruption, extreme poverty, the memory of recent wars, ethnic or religious imbalances, foreign interference, etc. Furthermore, the origin of conflicts is generally political and it is therefore no use addressing these issues without contextualising them in the search for a political resolution which contributes to peace.

The case of the east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo is one of the most serious because, in addition to this confluence of social and economic factors, the mining and smuggling of minerals represents an important source of financing for armed groups and this makes bringing peace to the area and an end to the human rights violations difficult.

How is a mine certified? How does a certified mine differ from one which is not certified?

At present, the organisation responsible for mine certification is the International Conference of the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR). Its Mineral Tracking and Certification division is responsible for ensuring that minerals entering the legal circuit come from conflict-free mines and comply with some minimum social criteria (e.g. that there is no exploitation of children). ICGLR certification ensures that a mine inspector from the government visits certified mines once a year. These inspections are verified by an independent annual audit. The mines are classified according to three colours, depending on their conditions:

1. Green flag: the mine complies with all of the standards (e.g. there is no armed presence or child exploitation) and can therefore produce minerals for legal exportation.

2. Yellow flag: there are infractions with regard to one or more important criteria and the mine operator has six months to resolve the situation. The mine can produce minerals for exportation under that condition.

3. Red flag: given the serious infractions with regard to one or more criteria, the mine is prohibited from producing minerals for at least six months until the next inspection confirms that the infractions have been resolved.

More information here. With regard to the problems with certification and the progress made, see question no.4.

Does certifying minerals at source work? What progress has been made? What still needs to be done?

International legislation encouraging the responsible supply of minerals from conflict zones has incentivised the development of systems of mine certification and labelling at source. The aim of these systems of traceability is to ensure that the minerals come from a “green” mine, i.e. one where the most basic human rights are not being violated.

The first certifications were done in 2014. Since then, the system has drawn criticism which needs to be considered. The first mining cooperatives that were created are controlled by the elites and do not end up being run democratically, the miners have no power when it comes to negotiating prices and the lack of transparency is worrying.

Despite the enormous challenges, some significant progress has been made. According to the United Nations, in 2010 all of the mines in the east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo were under the control of armed groups. In 2015, 44% of the 1,615 mines visited by IPIS Research had been demilitarised.

In order to achieve further progress, we believe that it is necessary that measures complementary to international legislation be implemented: see question 16.

Are conflict minerals only in Africa?

Not necessarily. A mineral such as coltan can be found in countries such as Australia or Canada, where its mining has not been linked to the financing of armed groups or organised crime. The relationship with human rights violations is what leads to a mineral being defined as a “conflict mineral.” At present, the existence of conflict minerals has been documented in various places around the world. However, acknowledgement of the problem varies depending on the international regulations and the interests of each country.

For example, the US has restricted its legislation on conflict minerals to four specific minerals (tin, tungsten, tantalum, and gold) provided that they originate in the Great Lakes region of Africa, since it is there where this link is most obvious. However, there are also conflict minerals in parts of Latin America and Asia.

In this regard, the European legislation that was approved in 2017 and which will come into force in 2021 is more ambitious in its geographical scope. The plan is to include a list of conflict zones (the CAHRA list of Conflict Affected High Risk Areas). It has not yet been defined which regions will be included, but it is likely that some areas of Latin America and Asia will be included, as well as the Great Lakes region of Africa.

What electronic devices are manufactured using these minerals?

Virtually all state-of-the-art electronics include components made from tantalum, tungsten, tin and gold, as well as many other raw materials of mineral origin. We are talking about consumer items such as mobile phones, computers, tablets, light bulbs and jewellery, but also the vast majority of electronic components (chips, capacitors, batteries, etc.). These are used in cutting edge sectors which are rapidly becoming more and more technically complex, such as microelectronics, telecommunications, surgical robotics and the aerospace industry.

What is a supply chain?

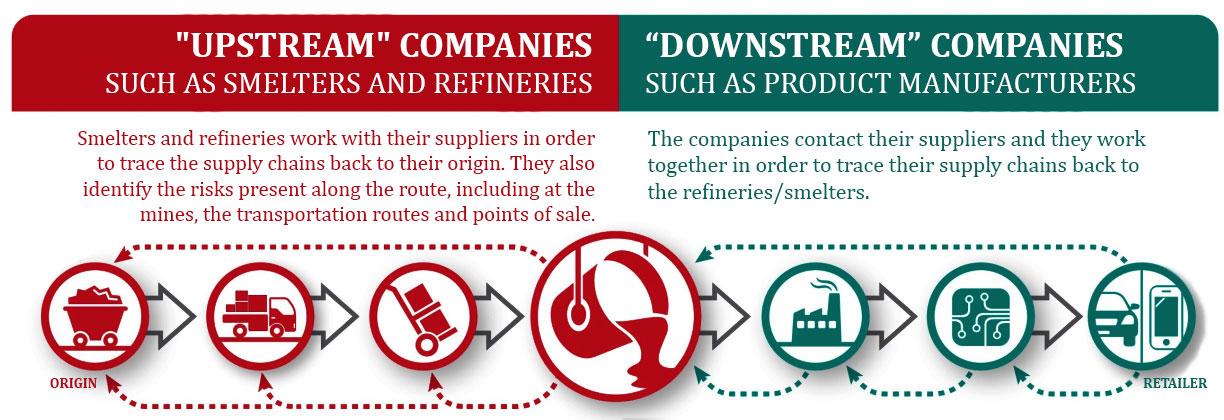

The term “supply chain” refers to all the actors (and their corresponding activities) involved in the process of manufacturing a product, from the extraction of the raw material to manufacturing to adding the finishing touches. In a globalised economy, many industries require supply chains which span multiple continents, as is the case with textiles, food and the electronics industries.

In the case of the electronics industries – which are the ones we address in the Conflict-Free Technology Campaign – the strategic raw materials used are of mineral origin. The supply chains of these industries therefore include all the people involved, from extraction, transportation, bringing to market, smelting and/or refining of the minerals, to the manufacture of electronic components, their assembly and the sale of the manufactured products.

As can be seen in the following infographic, the companies that operate in the first sector, from the mine to the refinery/smelter, are referred to as “upstream”, while those that go from the refinery/smelter to the final consumer are called “downstream”.

Is there a certificate that guarantees me “100% conflict-free” electronic products?

No. At the moment there is no certification that guarantees 100% that the electronic devices are free from minerals from conflict zones. This is because establishing that this is the case is extremely difficult due to the complexity of the supply chains and the lack of incentives for technology companies to behave responsibly with regard to the trade of “conflict minerals”. There is more and more legislation being put into place so as to promote these responsible practices in different industrial sectors.

In the case of mineral trading, various traceability systems have emerged on the ground over the last few years (see question 4) and some companies have begun to request audits from the refineries and smelters with whom they work so that they identify the origin of the minerals

In this respect, the certifications and audits, even if necessary, are not enough. The flow of minerals from areas at high risk of conflict to the refineries and smelters is constant. The audits, however, happen at particular times. So there is a permanent risk that a batch of minerals which has been extracted illegally or which is connected to human rights violations will be mixed with another of legal origin along the way.

Here at the Conflict-Free Technology Campaign we want a long-term commitment on the part of the company in which they adopt the principles of due diligence set out by the OECD. By doing so, the company shows its willingness to manage its supply chains responsibly. To learn more about how these principles are translated into law you can click on the “Regulating the trade in conflict minerals” link here.

How can I know if a company is behaving responsibly with regard to the issue of “conflict minerals”?

Almost all companies which make electronic devices use conflict minerals (tin, tungsten, wolfram, gold) in the manufacture of their components (chips, motherboards, batteries, capacitors, etc.). To find out if they are taking measures as regards the responsible supply of these minerals, you can search on Google for their policies concerning conflict minerals. If you do not find anything, it is a bad sign.

In the United States, for example, the Dodd-Frank Act (Section 1502) requires them to publish their conflict mineral reports annually. To date they have published two editions (the latest one is from 2016).

Based on this information, ethical rankings have been compiled which compare the quality of the information in these reports:

- You can consult the NGO Responsible Sourcing Network’s report “Mining the Disclosures 2017” here.

- The rankings of the NGO Know the Chain are also available. These allow you to compare the companies’ accounts based on different criteria, as well as the traceability of their raw materials. You will find the information at this link.

- Enough Project, an american NGO, just published its 2017 ranking of responsible companies on its website.

- You can also check the information on the companies gathered in the reports and news published by Good Electronics.

- You can donwload the latest Greenpeace Guide to Greener Electronics 2017 here.

Can a mobile phone be made without “conflict minerals”?

It is very difficult, not to say impossible, to manufacture a state-of-the-art electronic device without using minerals such as gold, tin, tungsten or wolfram, to name but a few of the most commonly used. The tantalite that is extracted from coltan, for example, is used to make electric capacitors. These can also be made from other materials (such as ceramic or aluminium), but tantalum has the unique qualities of resistance to oxidation and conduction of electricity and it takes up less space.

In this sense, it is not a question of avoiding the use of these minerals in the manufacture of electronic devices, but rather that the manufacturers and all the companies involved in their supply chains take the necessary measures so that they are not contributing to the financing of armed groups or the violation of human rights.

As of today, the company which is most exacting in terms of its ethical and environmental standards is Fairphone. Unfortunately, they only manufacture mobile phones and there are no similar initiatives in the areas of tablet or computer manufacturing. However, if you want the other companies in the electronics sector to follow their lead, sign our petition and we will use it to generate the demand for conflict-free technology.

What product (mobile phone, computer, etc.) will I buy?

If you are familiar with the humanitarian situation behind consumer electronics, it is likely that you have considered various options when it comes to buying. At ALBOAN, we believe that this is a highly personal decision which depends on many variables. We do not want to influence your choice, but rather give you the maximum information possible so that you can choose freely.

And since freedom is not possible without taking responsibility for our actions, we want to offer you the greatest amount of information possible so that you can make your choice. At ALBOAN we encourage you to consider other ethical and environmental criteria, and not just the price. In question 9 you will find some useful sources of information.

You can also consult our Guide to Responsible Consumption . And if you would like companies to provide more information in this regard, sign our petition and we will use it to generate a demand for Conflict-Free Technology.

Where can I bring my phone/computer/tablet to be recycled?

As part of the Conflict-Free Technology Campaign, we wish to promote responsible consumption practices among citizens. That is why we drew up the Guide to the Responsible Consumption of Electronic Products and launched the “Mobiles for the Congo” initiative – to provide private and public entities with the option of recycling and/or reusing their mobile phones.

Click here and find out how this initiative works.

If you want to dispose of other electrical or electronic devices, you can contact the Spanish Association of Recuperators of Social Economy and Solidarity (AERESS[KC2] ). They are a state platform of charitable institutions dedicated to the reduction, reuse and recycling of waste, with the aim of social transformation and the promotion of the socio-occupational integration of people in situations of social exclusion or at risk thereof. They can give your appliance a new life and resell it second hand, while at the same time generating employment in your area.

If, on the other hand, it is not possible to salvage or recycle your device, we recommend that you contact the department of your local council responsible for environmental issues so that they can direct you to your nearest green point.

How I can get one of your boxes for recycling mobile phones?

At this Mobiles for Congo initiative link you will find the necessary information.

Topic: Legislation on conflict minerals

Why is it necessary to regulate global trade?

The acceleration of economic globalisation in the 1990s contributed to the relocation of many industrial sectors and the concentration of business around large multinational companies. Today, many consumer products (from food to textiles to the minerals incorporated into our technology) are manufactured from or require raw materials which are found beyond our borders. This would not be possible without the creation of global supply chains (see question 7).

The problem is that corporate relocation practices and the internationalisation[KC1] of industries have often been driven by the advantages (access to cheap raw materials, the lack of environmental regulations, low labour costs, etc.) to be gained from operating in those countries with weaker legislation.

In order to prevent these trade practices from resulting in the violation of human rights, the United Nations adopted the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business[KC2] and Human Rights. The challenge is to turn these voluntary principles into binding regulations.

How can trade in “conflict minerals” be regulated?

If you go to our website, under the tab What is TLC? you will find a section called “Regulating the Mineral Trade” where we answer this question by telling you about existing regulations and laws to promote the responsible supply of minerals.

Is European law enough to bring an end to the humanitarian crisis in eastern DR Congo?

No. The humanitarian crisis has political roots and must be resolved by political means. The aim of European law is to promote responsible supply practices among the EU-based companies that import these minerals from conflict zones, such as the eastern DRC. In this sense, the law is an important step but, as we said when the agreement was reached, we believe that it is not enough.

For this legislation to have a positive impact on the Congolese communities living from artisanal mining, it is necessary for the European Union to implement accompanying measures aimed at improving the good governance of the mining sector.